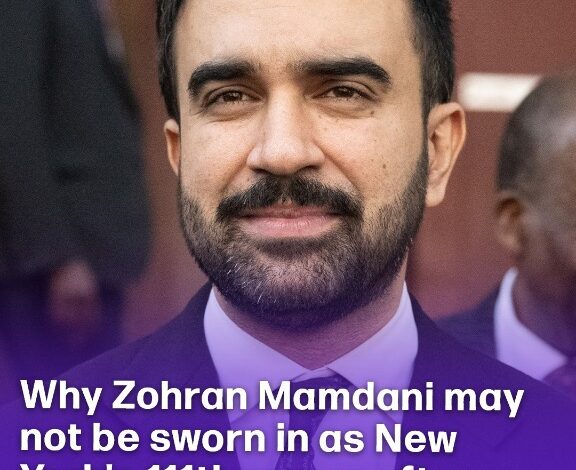

Why Zohran Mamdani may not be sworn in as New York 111th mayor after shocking detail emerges

Zohran Mamdani’s election wasn’t just another political milestone—it was a tectonic shift in a city known for its noise, chaos, and contradictions. At 34, he broke through every barrier New York had been slow to confront: the first Muslim mayor, the first of South Asian descent, the first born on African soil. His win felt like the city finally catching up to its own identity. The inauguration was set for January 2026. The energy across the five boroughs leaned forward, ready for history.

And then an obscure detail cracked open a quiet, centuries-old mistake—one so bizarre that it temporarily overshadowed the biggest mayoral win in modern memory.

The discovery came from historian Paul Hortenstine, who had been sifting through records while studying New York’s early entanglement with the transatlantic slave trade. Buried in those archives was a mayor whose existence everyone knew about—but whose terms nobody had counted correctly. Matthias Nicolls, New York’s sixth mayor, didn’t serve one term. He served two, years apart—1672 and 1675. But instead of listing him twice, recordkeepers lumped his terms into one continuous entry.

That tiny clerical shortcut, made before electricity even existed, meant every mayor after Nicolls had been numbered wrong for 351 years.

If Nicolls’s terms were counted separately—as the city counts all non-consecutive terms, including for governors and presidents—New York’s incoming “111th mayor” wasn’t the 111th at all. Mamdani would actually be the 112th.

Hortenstine didn’t sit on this information. He notified city officials, sent documents, and flagged the historical oversight. The strange part? He wasn’t the first to notice. Back in 1989, historian Peter R. Christoph pointed out the same discrepancy. His warning was ignored, dismissed as an unimportant technicality. The error simply calcified into tradition, and every subsequent administration repeated it without question.

Until now.

With Mamdani preparing to take office as one of the most symbolically significant figures in New York’s history, this odd revelation hit differently. It wasn’t political. It wasn’t legal. It wasn’t even controversial, really. It was simply… bizarre.

Would New York fix a 350-year-old mistake? Would Mamdani be sworn in as the 111th mayor out of tradition, or as the 112th mayor according to the actual historical record? Would the city renumber every mayoral list, plaque, portrait, archive, and ceremonial reference dating back to the 1600s?

Suddenly, a footnote became a talking point.

Some New Yorkers laughed it off—“Of course the mayor count is wrong. Why wouldn’t it be?” Others felt embarrassed that such an old oversight lingered in a city obsessed with accuracy and documentation. The archival community lit up with debate, arguing about whether correcting history late was better than leaving it wrong forever.

The bureaucrats, meanwhile, cringed. Fixing the count meant rewriting centuries of institutional material: museums, textbooks, government websites, internal filings, even mayoral gifts and portraits. A nightmare of red tape. A headache no office wanted to own.

But none of this changed a single thing about Mamdani’s power, authority, or legitimacy. His election was decided by voters, not numbering. His oath would be the same. His responsibilities would be the same. The discrepancy lived entirely in symbolism—half historical curiosity, half bureaucratic comedy.

As the story gained traction, Mamdani reacted with the kind of calm New Yorkers had started to associate with him. At press conferences, reporters tried to push the numbering drama. He brushed it off, redirecting the conversation to housing, transit, school safety, economic recovery—issues that actually moved people’s lives. If anything, he treated the miscount like a quirky anecdote in an otherwise intense transition period.

The real arguments unfolded behind closed doors.

Archivists and historians sparred over accuracy. Public-facing departments questioned whether the ripple effect of correcting the count could cause confusion. Curators at the Museum of the City of New York debated whether the mayoral timeline exhibit would need a renovation. Lawyers clarified that ceremonial numbering had no legal significance whatsoever.

But Hortenstine pressed on. To him, acknowledging the oversight mattered—not because the mistake harmed anyone, but because history should be correct, even when inconvenient. Christoph’s research in 1989 deserved recognition. Matthias Nicolls’s second term deserved recognition. And New York’s archives deserved precision.

Meanwhile, city residents treated the saga like a peculiarly New York kind of entertainment—a reminder that even in moments of progress, the city’s past has a way of resurfacing to complicate the present. It became dinner-table conversation, bar chatter, subway banter. “Only in New York,” people said. “Only here could the mayor count be wrong for three centuries.”

In the weeks before Mamdani’s swearing-in, the dispute settled into a strange kind of limbo. Journalists wrote about it with amusement. Political analysts shrugged at its lack of real consequence. Historians argued that the city should at least acknowledge the discrepancy, even if it didn’t formally renumber anything.

And still, Mamdani kept his focus exactly where it needed to be: the work ahead.

Housing policy. Transit reliability. Policing. Job growth. Education. Economic stability. Representation. The numbering confusion didn’t shake him or distract him. If anything, it underlined a theme of his candidacy: New York’s future doesn’t depend on what the city has always done. It depends on what it decides to do now.

The clerical error, however, carried symbolism. It showed how history evolves, how easily inaccuracies become tradition, and how even the smallest overlooked detail can outlive dozens of generations. It reminded New Yorkers that their city, as mighty as it appears, is still shaped by messy human hands—hands that misfile, miscount, and occasionally forget.

When Mamdani steps up to take the oath, he’ll inherit a city perched between old habits and new realities. Whether the podium plaque reads 111 or 112 won’t change the weight of the moment or the challenges standing in front of him. New Yorkers will be watching the future, not the number attached to his title.

But one thing is certain: thanks to a dusty archival quirk dug up at exactly the wrong—or right—time, historians will be arguing about the numbering of New York’s mayors for years to come. A footnote has officially become part of the city’s story.

And in a city built on reinvention, even the fine print matters.